A Non-Technical Introduction to Docker

When life gives you containers.

How to run the perfect lemonade stand, every time

Docker is a tool that allows you to define and contain everything needed to make an application run, as well as the tools to run that application in a way that will be consistent outside of the environment it was developed in.

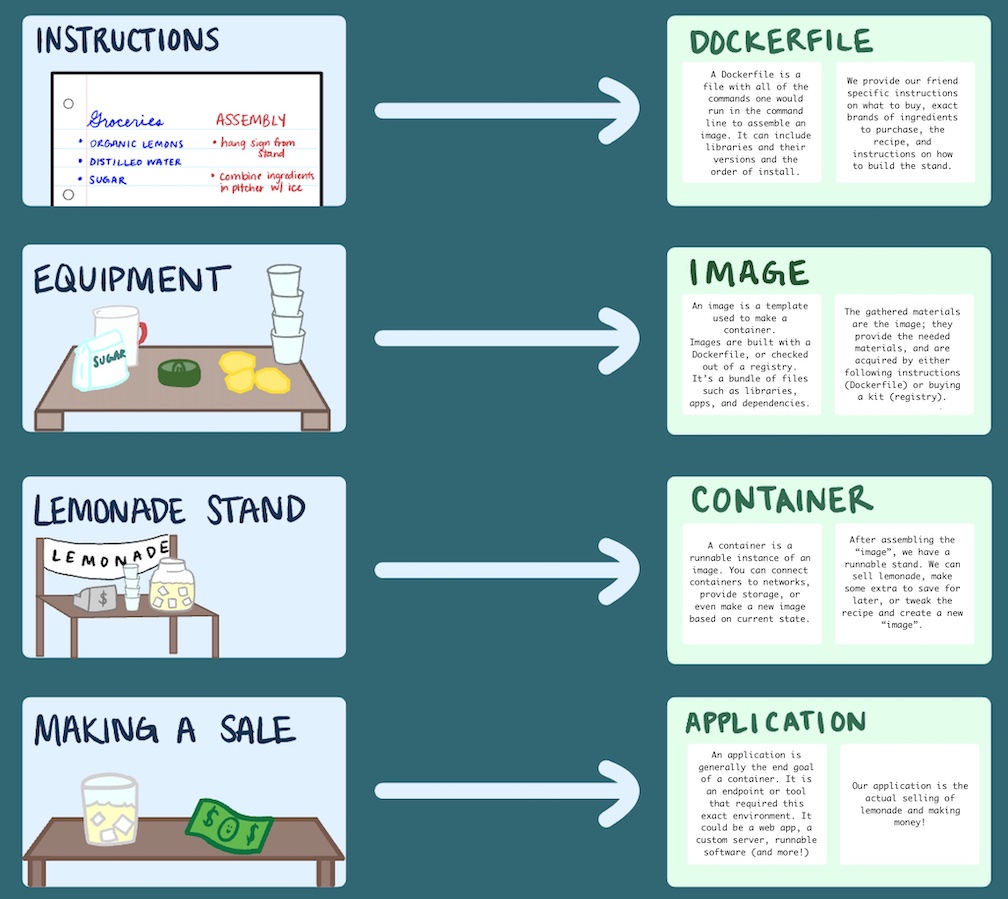

Rather than an application on a computer, imagine we are running a lemonade stand. Everything about it - the logo, the cups, the lemonade recipe - is so successful that we want to allow our friends to reproduce it exactly, without needing to guess about our methods. We will first write down all of things we had to buy to run our stand (the type of table, the brand of sugar, the color of the cups) in extreme detail. This is our Dockerfile. It is the manifest that will allow everyone to reproduce our lemonade stand exactly.

Let’s say we have given our Dockerfile to a friend so they can make their own successful lemonade stand. They follow the specific instructions we give them and purchase everything listed in the file, in the order we specified. Now they have a table, chairs, cups, ice, and lemonade ingredients on their lawn. We can think of these raw supplies as an image. In Docker, the Dockerfile tells us exact instructions on how to “build” an image. In our example, our Dockerfile told us exactly how to purchase our ingredients and setup our stand. Our friend can even store the “image” - the supplies and ingredients - when they are done, so the next time they want to run the stand, they have everything they need.

We could also package the supplies we use for our lemonade stand, and offer to provide these packages to people who want to make and sell our exact kind of lemonade. People could logon to our website and order a kit to make their very own lemonade stand. Because we are the ones creating the package, when someone buys it, they will get the exact same lemonade supplies and be able to make the stand to our exact specifications. Now, let’s assume that there is a website where folks can sell all kinds of these kits, each with their own variations. This would be equivalent to a Docker registry. Anyone could place their own kits of supplies (their images) onto the registry. When someone buys one (or checks an image out of a registry), they are able to exactly reproduce the intent of the seller.

The last step is to simply run our lemonade stand! This will require a person to man the stand, make the lemonade from our specified recipe, and sell lemonade to customers. This functioning stand is our container - it is a contained instance of our successful lemonade franchise. In Docker, a container is defined as a “runnable instance of an image”. Generally, a container exists to run an application. In our case, the application is the selling of lemonade to passers by.

While there are some idiosyncracies that make this example slightly different, it’s overall a decent encapsulation of the big idea of Docker - we define a set of steps and ingredients (possibly libraries and packages) in a written manifest (Dockerfile) that tells someone what to purchase and how to set it up (an image), such that once they follow the instructions in our manifest, they can run the lemonade stand (the container) and sell lemonade (the application).

What’s the big deal?

Our goal in this example isn’t simply to setup our own lemonade stand, run it once, and never think about it again. Our goal was ultimately to allow anyone to run the same lemonade stand, so long as they had all of the right materials, and be able to run it again and again, having the lemonade taste equally delicious and sell just as well. If we made the lemonade and mailed it, it would taste right by the time it got there. If we told them the recipe but weren’t specific about the brand of sugar or the ripeness of the lemons, they might make it differently than us. If they have the exact recipe, but don’t know how we assembled the stand itself, they might not have the right equipment to draw in the same number of buyers.

The idea with Docker is the same. If we develop an application entirely on our local machine, deployment then becomes really complicated - if we want someone else to be able to run our application on their machine, how will we know that it will work exactly the same? The answer is that we can’t - unless of course we send them our whole machine.

That is the essence of Docker. It defines a contained “machine” on which an application will run. This way, instead of sending someone a few Python files and telling them to run it, we can also send them the environment that they will run those files on, ensuring that the code will work exactly the same no matter who we send it to - it will always be running in the exact same environment, within the container that we have defined.